11

N Sathiya Moorthy

Chennai | Wednesday | 11 March 2025

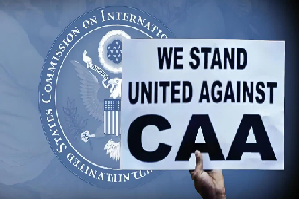

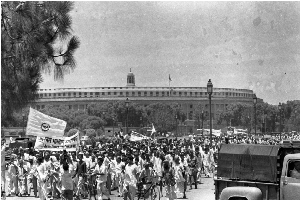

The uninitiated from across the Vindhyas may have been wondering as to the sudden spurt in what some of them may have once again concluded as an anti-North, and at times ‘anti-national’, ‘Dravidian political protests’ that has no relevance in the 21st century ‘India that is Bharat’ or ‘Bharat that is India’. Just as they may complain that the present-day Tamil generation (too) is being burdened by the baggage from around the time of Independence, pre- and post-, theirs too is even more scarred by the burden of a past that they had understood very little, then or since.

To begin at the beginning, the recent Tamil protests, centred on ‘de-limitation’ and ‘Hindi imposition’, have had a long history. The two are independent of each other but together contribute to triggering the revival of ‘Tamil identity’ politics that was long since forgotten around the turn of the new century/millennium. During that interregnum, the Dravidian political identity, cutting across different electoral identities, had moved on and away from entrenched ideology from a decades past to a more identifiable competitive developmental programmes while in elected power.

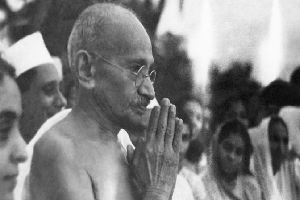

To begin with, the mainstreaming of the DMK, which had propagated a separate ‘Dravida Nadu’, inherited from the party’s ideological forebear in the DK of ‘Periyar’ E V Ramaswami (EVR), and the party’s subsequent elevation to elected power in 1967 showed how the Indian constitutional scheme could absorb them effortlessly and also had inherent provisions for accommodating their diverse and diversified socio-political ideology. Suffice to recall and remember that what is celebrated or condemned as the Dravidian socio-political ideology is older than the and in effective practice had been around for over a quarter century before the nation attained Independence, before proclaiming itself a Republic before going onto formulating ‘linguistic States’, both within the first decade of Independence.

Historically, Tamil Nadu had been developed for centuries before the British colonial rulers took control. It is true that the state and/or the region did not fall victim to the ravages to the succession of invasions from across the Khyber Pass. But then, the story of the state’s social, political, economic and cultural growth and development under the Cheras, Cholas, Pandyas and Pallavas date to a period before the arrival of Babur but definitely included the era since the advent of the ‘Slave Dynasty’ and Delhi sultanates.

There is also true in the geographical truth that coastal nations/states often flourish while their hinterland remains a poor cousin. However, there is no comparison between ‘ancient India’ and the rest of the developed East and West, namely, present-day Odisha and Gujarat. Like the present-day Tamil Nadu, they have had a long and successful career in maritime trade and consequent prosperity. Of course, there is no parallel in Indian history to the Cholas’ sending their troops to neighbouring Sri Lanka and distant South-East Asia as far back as the 10th and the 11th century.

In comparative terms, Tamil Nadu alone between the three could sustain the momentum and grow, without break. Gujarat caught up with Tamil Nadu first and has overtaken it since, just over the past couple of decades or so. Unfortunately, Odisha fell into bad times generations and centuries ago, but has not been able to retrieve the lost ground and glory.

All this meant that mostly undisturbed by the wars and violence elsewhere, the Tamil society was moving forward in social indicators of whatever kind that was available at the time. This only progressed under the British Raj, for which Chennai, then Madras, was the first capital, before they moved first to Calcutta, now Kolkata, and later Delhi. In turn, this meant a new socio-political awakening that led to the advent of the ‘social justice’ movement as far back as the turn of the 20th century. This in turn caused the institutionalisation of caste/religion-based job and education reservations under the Raj, as far back as the 1920’s.

Meeting national goals

It is in this overall background and context, the current ‘crisis issues’ need to be studied and understood. Whether you like it or not, ‘Dravidian political identity’ is older to the larger ‘national identity’. The complaint, whether right or wrong, is that enough has not been done to wholly integrate the same into the national matrix. Whenever there is a discourse, debate or differences over the subject, the blame-game too gets kicked off, with ‘nationalists’ blaming the Dravidian politicians and ideologues, and the latter serving the ball back to the Centre’s court.

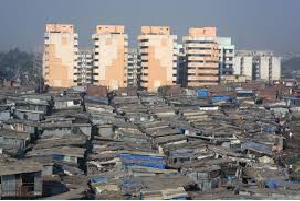

This is precisely what has happened this time, too. For instance, the de-limitation row is centred on a larger Tamil grouse that the state is being continually penalised from developing first and then faster, and such development and growth positively impacting social indicators. As a sign thereof, critics of the existing seat-sharing scheme for national-level elections to the Lok Sabha point out how the State’s share of the national cake has been dwindling owing to the failure of other States to meet national goals in time and effectively so.

When DMK Chief Minister M K Stalin, whose coinage of ‘Dravidian model’ is yet to find resonance in other parts of the country, that too cutting across alliance politics and party lines, eyebrows were caused to be raised why he was reviving the ‘de-limitation’ debate without notice, without provocation. And why none of his Dravidian allies and adversaries alike too were not questioning the timing, a year ahead of the assembly elections, when he could do with some diversionary tactic, to ‘pull the customary wool over the eyes of the voters’?

The unsaid reason was plain and simple. With the 2021 Census already delayed, owing to the Covid pandemic and lockdown, followed by the long run-up (?) to the Lok Sabha elections of 2024, there is now apprehension if the BJP Centre could play any ‘irretrievable mischief’ over fresh ‘delimitation’ after further delaying the national head-count. This is because Article 82 of the Constitution, dealing with Delimitation, was amended by the third Vajpayee Government (1999-2004) after the BJP-NDA’s Tamil Nadu allies, comprising the DMK (yes!), MDMK and PMK, protested the inevitability of injustice that any immediate delimitation would cause.

As they pointed out, any immediate delimitation, based on the decennial Census due in 2001 would cause a steep fall in the number of Lok Sabha seats from 39 to 31, for Tamil Nadu. Neighbouring Kerala too made feeble protests that theirs would go down from 20 t0 15. They saw it as penalising their respective development models, which also included women education, empowerment and awareness, and overall growth and development of the States compared to counterparts elsewhere in the country.

Considering the impossibility of the situation, rather than the fear of the Government’s BJP partners threatening a pull-out, Prime Minister Vajpayee did the next best thing. The Government caused Parliament to amend Article 82 to put off delimitation at least by another 25 years. Accordingly, no fresh delimitation was possible until fresh population figures are available as per any ‘Census conducted after 2026’. Ordinarily, this would mean that there was no cause for the Dravidian parties in Tamil Nadu to protest delimitation now, as the effect of the postponed Census from 2021 to 2025 would come into force before 2026, and any fresh delimitation can be attempted only in the next round of Census. It could be either 2031, as should have been the case under the old scheme, or any time later, if the BJP Government at the Centre decides to dump one more of the nation’s ‘colonial legacies’.

Pre-meditated, pre-determined

Herein lies the Dravidian hitch. First, whenever delimitation is undertaken, Tamil Nadu’s complaint about the emerging inequity in seat-distribution was genuine and had to be addressed. States like Kerala, Karnataka and Telangana, all of which are ruled by non-BJP parties, all of which are development success stories that have also managed their population growth rates well through the past decades. Though the Government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi had allocated ₹ 8000 crores for the decennial Census as far back as 2019, and even wanted the head-count to be completed a year ahead of the previously followed time-line (that is 2020), there is no talk three months into 2025 about undertaking a fresh head-count even now.

Incidentally, there is comparable concern, again unmentioned, about the possible revival of the controversial National Population Register (NPR) project, for which again the Modi Cabinet had allocated ₹ 3000-plus crores in 2019. Now that the routine biennial Census did not take place when due by 2021, there are apprehensions if the NPR would be revived as and when fresh population figures become available.

In the interim, though not spoken about, doubts have arisen about the possibility of the BJP Centre delaying the Census beyond 2026, and cite the amended Article 82, to hurry through a ‘pre-meditated, pre-determined’ delimitation for the Lok Sabha polls that are due in 2029. The hurried nature of the process would not give the nation and institutions adequate time to review the ground realities, even if moved. Such a move, if there is one, some Tamil Nadu critics call as ‘devious and dubious, if not diabolic’.

Honourable way out

The issue does not end there. There is another document called the National Population Policy, the last one of which was released in 2000 (NPP-2000). It guides the authorities on population-management. The document had fixed 2045 as the deadline for ‘population stabilisation’ across the country. This does not mean that the population figures or even growth-figures in a large and backward State like Uttar Pradesh or Bihar would have levelled out with those of Tamil Nadu or Kerala. It only meant that there would have been some kind of equitable growth-rates, hence a certain fairness on decisions based on population growth and spread.

Now, with the Modi Government having provided 888 seats in the Lok Sabha and 384 in the Rajya Sabha, in the new Parliament Complex, the question remains how the Centre intends filling them up – whether through fresh delimitation based on new population figures, or by providing 33-per cent reservations for women, over and above the current strength or a combination of both or under any other formula that remains a secret. Either way, any delimitation based on population figures might also entail an equitable cut in the number of SC-ST reservation seats in the States that would suffer a fall in the total number of seats.

Overall, it may be compensated by the relative increase, or even more in the number of reserved seats in States where population figures commanded an increased total. However, given the denominational differences and differentiation, including that of language and culture, within the reserved groups in individual States, the loss in one State could not be construed as capable of being compensated elsewhere.

Today, when the all-party meeting called by CM Stalin has sought fresh delimitation to be put off by another 30 years without reference to proviso 3 of Article 82 as amended, it’s a honourable way to put off the inconvenient national question to another day – and yet again. Before Vajpayee’s time, the Constitution was amended unanimously in 1971 to extend SC-ST reservations, which was built into the Constitution at birth, by 30 years – to the year 2000. More importantly, it implies that 30 years from now, that is by the year 2025, ten years would have passed after the 1945 deadline for ‘population stabilisation’ would have passed, and there could be a fresh National Population Policy based on new figures and circumstances.

Yet, it would not address all of Tamil Nadu’s current concerns but at least the nation would have time to think over things, unlike the wasted 25-year deadline set by the Vajpayee Government. It is another matter that the Modi Government, in its first innings, had disbanded the ‘Group of Ministers’ (GoM) system put in place to monitor the implementation of NPP-2000, so as to guide and monitor the promised goal of ‘population stabilisation’ by 2045.

It is anybody’s guess if and if so how many times that the GoM had met or what work it had done before Modi’s time. To be fair, the Modi dispensation had disbanded the NPP-2000 GoM as a routine matter along with such other GoMs, but did not seem to have reviewed each case to name a fresh GoM to undertake the work assigned to them with a future deadline in mind.

Deny pride of place

If this is the case with delimitation, where does the issue of ‘Hindi imposition’ crop up? The immediate provocation came not from any Dravidian entity but from Union Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan. Responding to Tamil Nadu’s repeated appeals to release ₹ 2000-plus crore amount due to the State under the ‘PM-SHREE’ scheme, Pradhan public said in the controversial ‘Tamil Sangamam’ annual conference project in Modi’s Varanasi Lok Sabha constituency, that those funds would be available only to States that implemented the Centre’s ‘New Education Policy’ (NEP). The NEP, inter alia, sought to impose a three-language formula on Tamil Nadu, which has had a chequered history of a ‘two-language’ scheme.

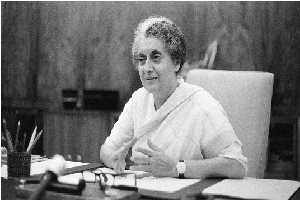

Accordingly, Tamil Nadu has always taught its students only Tamil and English, and Hindi remained optional until the DMK Government of 1967 did away with that facility – only to reintroduce the scheme selectively as times passed by. The Tamil Nadu scheme has clearly stated that the State was not against Hindi education but was only opposed to ‘Hindi imposition’ as is being sought through the NEP now and through Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri’s initiative in 1965, when the State erupted.

The perception is that Shastri took up the issue for going to the (north Indian) voters over the heads of the ruling Congress ‘syndicate’ that was emasculating him. Against this, the fear now is that the BJP Centre is trying to re-write Indian history with their own version, so as to make Hindi the ‘national language’, and deny classical languages like Tamil their pride of place in history and the daily life of millions of people – possibly forever.

Today, Dravidian political leaders are alive to and aware of the rekindled ‘Tamil pride’ in the new generation that was not present until before the advent of the unprecedented ‘Jallikattu protests’ of January 2017, which was as much apolitical as it was youthful and self-driven. Included in the undrafted youth agenda is perception of the Centre wanting impose not only Hindi, but through it ancient Sanskrit, at the cost of Tamil, for instance, when the Vedic language has few uses in the daily life of the average Indian anywhere in the country unlike their own language that has been alive for centuries together without break.

Job opportunities

It is here those propagating the ‘three-language formula’ in Tamil Nadu, noticeably the BJP-RSS types, fall short in their arguments. As the other side has been pointing out, the argument that by denying Hindi-learning successive State Governments are denying North Indian job opportunities for the people of Tamil Nadu, is bad in practice.

They point to the ground reality as to how the children and grandchildren of most front-line BJP-RSS leaders in the State, who were denied Hindi-learning but still benefited from the two-language formula, are settled in English-knowing West, and not in any of the North Indian States, as assumed. They further argue how Hindi-knowing North Indians, cutting across social and educational strata, are getting gainful employment in Tamil Nadu and other South Indian States – and not otherwise, as claimed.

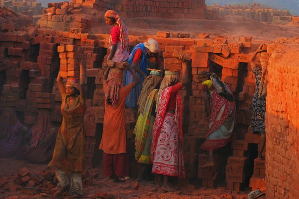

If these are academic issues, on the ground, successive State Governments have been arguing the case of rural students from poor families that have to shell out extra money to truly equip their wards in the learning of Hindi, which is not a spoken language in their environment. The same applies to the learning of English, but given the long history of English-teaching since before the days of the British Raj proper, there is at least a certain open-mindedness at the societal level. The same cannot be said of Hindi-learning.

It is in this context, the insistence of Hindi-learning under NEP has become problematic. Even without Hindi, Tamil Nadu is opposed to a graded system of board exams every three years or so, that tend to make children robots, denying them their childhood. It is also against the new ideas emerging from across the world regarding child-upbringing to make them more responsible and responsive citizens as they grow up.

As an aside, the argument goes how the NEP seeks to put the Hindutva thoughts about Bharatiya Sanskar in child-upbringing and the traditional joint family system, by placing a high premium on competitive upbringing. Anyway such a competitive environment in learning and living is an anathema to this political class, which has always dubbed and derided the inherited ‘colonial educational scheme’ and have been blaming the predecessor Congress leadership and Governments for the same.

It is here that a majority of Tamil Nadu polity and society link the Centre’s ideas such as NEET first and NEP since as legal tools to ‘suffocate’ aspirational states and their population that have already broken away from monotony of slow growth elsewhere along with its negative consequences. High birth-rate is only one of them. The post-Jallikattu contention, dating it back to the advent of ‘hard-line Hindutva’ under the present BJP Governments at the Centre and in most States across the country, is that there was a deliberate ‘ideological attempt’ to deny Tamil, Tamils and Tamil Nadu their due.

As is being pointed out, Tamil Nadu has the highest per capita availability of medical doctors in the country, comparable to Nordic countries. This became possible through the opening of more medical colleges in the Government sector after private hospitals became high-cost institutions even when they were also of very high quality. Alongside, the State Government also opened up medical education to rural students after the State Government ended the era of entrance examinations.

The introduction of NEET, under the directions of the Supreme Court, it is still feared, has eroded the opportunities for rural students and those from poor family background as they cannot afford what has become a statutory need for having private tuitions that they could not afford, when the fee were in hundreds and thousands, and now when it is in lakhs – oftentimes, online. Some in the State also consider both NEET and NEP as devious products that would end up curtailing the opportunities available to the up and coming generations of Tamil youth, who are beneficiaries of the evolved yet graded scheme of Dravidian ‘social justice’ policy that has worked effectively through the post-Independence Congress era, too.

Pragmatic approach

Thus, whether it is delimitation, or Hindi imposition or the larger NEP/NEET implementation, it is not only Tamil pride that seems to have been hurt. There is also a seeming pragmatic approach to them all and they have been inherent for a long time. This anxiety, fear and suspicion have been accentuated by the advent of the Hindutva rule at the Centre and their ideology-driven national agenda that has become even more possible with the Government’s strength in Parliament – even if it is not BJP-exclusive as during the first two terms of the Modi Government.

The apprehension is that just as the BJP has gone through the ‘Hindutva’ project near-effectively through the past 10 years, there is a ‘sinister move’ to create a ‘harmonious’ Indian society and nation, deviating vastly and at times violently, from the First Principles of ‘Unity in Diversity’ and institutionalise it at all levels before the BJP and/or its present national leadership loses out further in electoral politics, owing to the sheer boredom of the voters and /or inevitable anti-incumbency that was touched and felt in Elections-2024.

At the time, the party could not obtain an absolute majority on its own, despite hard-selling for months and years and running down political rivals systematically and so very completely through the same period. Thereby hangs a tale!

(The writer is a Chennai-based Policy Analyst & Political Commentator. Email: sathiyam54@nsathiyamoorthy.com)