2

Salman Ahmad

New Delhi | Monday | 2 June 2025

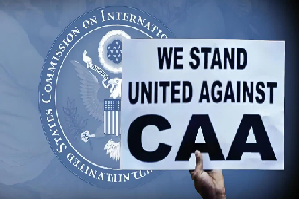

In a society that values justice and fairness, individuals should have the right to choose their food—so long as it causes no proven harm to themselves or others. Yet in India, food choices are deeply entangled with religion, caste, identity, and politics. What we eat has become a symbol of moral standing, cultural belonging, and even grounds for violence.

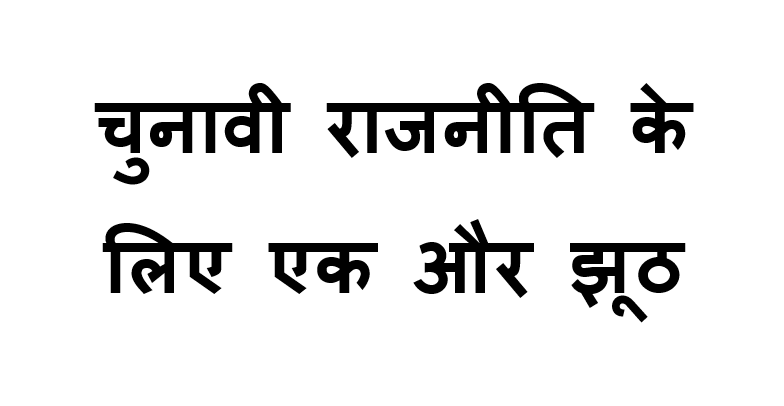

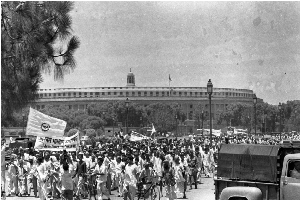

In recent years, a form of dietary fundamentalism has gained ground, particularly the imposition of vegetarian values by dominant social groups. This isn’t just about personal belief or animal rights—it’s a political assertion. Portraying India as a fundamentally vegetarian nation ignores the realities of its diverse population and marginalizes communities where meat is a staple.

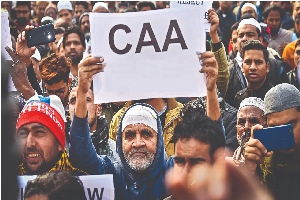

This narrative has reinforced social prejudices against Muslims, Christians, Scheduled Castes and Tribes, and people from coastal or northeastern regions. These groups, already facing systemic discrimination, now confront stigma over their dietary habits. In some cases, this has led to mob violence, often in the name of protecting tradition or religion.

Myth vs. Reality: What the Data Says

Globally, vegetarians are a minority. A 2018 IPSOS survey across 28 countries found that over 90% of people consume meat. In India, the reality is similarly diverse. NFHS-5 data (2019–21) shows that 83.4% of men and 70.6% of women aged 15–49 eat non-vegetarian food. These numbers have remained stable or grown over time.

Religion plays a role in shaping dietary norms, but the idea that only Muslims and Christians eat meat is a myth. In fact:

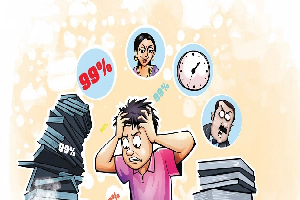

• 99% of Christians and Muslims, and 97% of Buddhists/Neo-Buddhists consume meat.

• Over 75% of Hindus eat meat, despite perceptions to the contrary.

• Even among traditionally vegetarian communities, 15% of Jain men and over 4% of Jain women reported meat consumption.

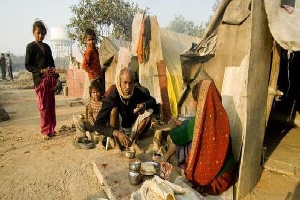

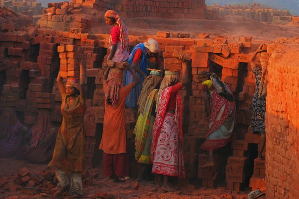

Class and caste further shape food patterns. 90% of India’s poorest eat meat, compared to 70% of the wealthiest. Among Scheduled Castes and Tribes, non-vegetarianism exceeds 87%, whereas among upper castes (“Others”), it’s closer to 72%. Meat is often more accessible and affordable in protein terms, especially in rural or tribal areas.

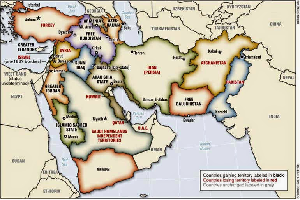

Regional Realities

Only four Indian states—Punjab, Haryana, Rajasthan, and Gujarat—are predominantly vegetarian. In contrast, northeastern and coastal states like Mizoram, Kerala, and Andhra Pradesh report non-vegetarian rates over 97%. In Tamil Nadu and West Bengal, fish and meat are dietary mainstays.

Urban-rural gaps and gender differences persist. In wealthier rural households, men are more likely to eat meat than women—reflecting gendered access to nutrition.

Religion and Food: A Nuanced View

Religious dietary rules are often more flexible than popularly believed.

• Hinduism does not universally prohibit meat. Ancient texts reference meat-eating and even animal sacrifices. Swami Vivekananda noted that, historically, beef consumption was part of certain Hindu rites.

• Islam permits meat but requires ethical slaughter. Halal emphasizes compassion and discipline in food practices.

• Christianity broadly permits meat, with ethical caveats around ritual sacrifices and treatment of animals.

• Buddhism varies widely: while some Mahayana sects advocate strict vegetarianism, many Theravāda and Tibetan Buddhists permit meat under conditions.

• Sikhism discourages ritual meat (like halal) but allows personal dietary freedom.

• Jainism has the strictest rules, based on ahimsa. Yet even here, some followers report eating meat, indicating a gap between doctrine and daily life.

These examples show that religious food norms are not monolithic. They evolve with time, region, and socio-economic context.

Is Eating Meat Barbaric?

The argument that meat consumption is cruel or uncivilized has gained currency in some circles, but it lacks nuance. Humans evolved as omnivores. Cooked meat played a crucial role in brain development, as shown in anthropological research by Richard Wrangham and others.

From a biological standpoint, human physiology supports both plant and animal consumption. Meat provides vital nutrients like B12, iron, and omega-3s—hard to obtain from plants alone, especially in low-income diets.

Moreover, cruelty is not exclusive to meat. Industrial crop farming causes deforestation, soil degradation, and ecological harm. Ethical reform should target how food is produced, not what is eaten.

Economic Backbone: The Meat Industry

India's meat and livestock industries are critical to rural livelihoods and national exports. In 2023–24, India exported $3.74 billion worth of buffalo meat, making it a global leader. The sector employs millions—from butchers and traders to transporters and small farmers.

Contrary to common perception, the beef industry is not dominated by Muslims. Key exporters like Allanasons, Al-Kabeer, and P.M.L. Industries are owned or co-owned by non-Muslims. The business is secular, driven by demand and trade—not religion.

Freedom vs. Food Policing

The real concern isn’t vegetarianism itself, but the attempt to morally police food choices. Elevating vegetarianism as a national ideal and stigmatizing meat-eaters fosters exclusion, particularly against minorities and marginalized groups. It also misrepresents India’s culinary heritage.

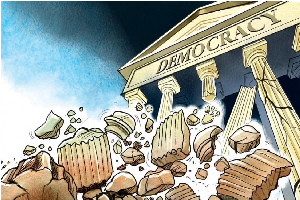

In a democracy, food should remain a personal choice. Imposing one dietary code through law, social pressure, or mob violence undermines liberty and pluralism.

Conclusion: Embracing Dietary Diversity

India is a land of diverse tongues, cultures, and tastes. Its food habits mirror this complexity. While vegetarianism is a valid and often noble lifestyle, it should not be wielded as a moral or cultural weapon. The politics of food must make room for mutual respect and informed choice.

In a world grappling with nutrition insecurity, climate change, and inequality, the focus should shift from what people eat to how food is grown, distributed, and accessed. Ethical, inclusive, and sustainable systems—whether plant-based or animal-based—are the way forward.

Ultimately, respecting food choices is about respecting people. And in a nation as diverse as India, that is the only sustainable path.

**************