14

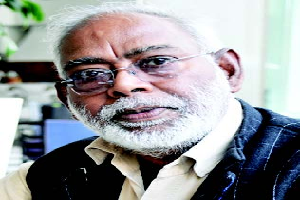

Prof Pradeep Mathur

New Delhi | Wednesday | 14 May 2025

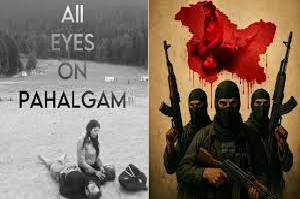

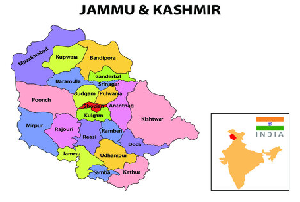

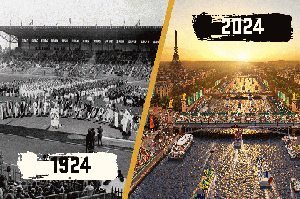

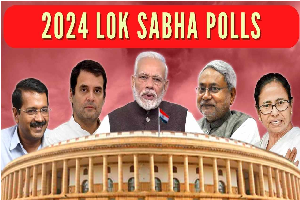

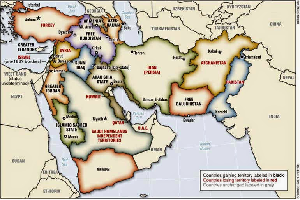

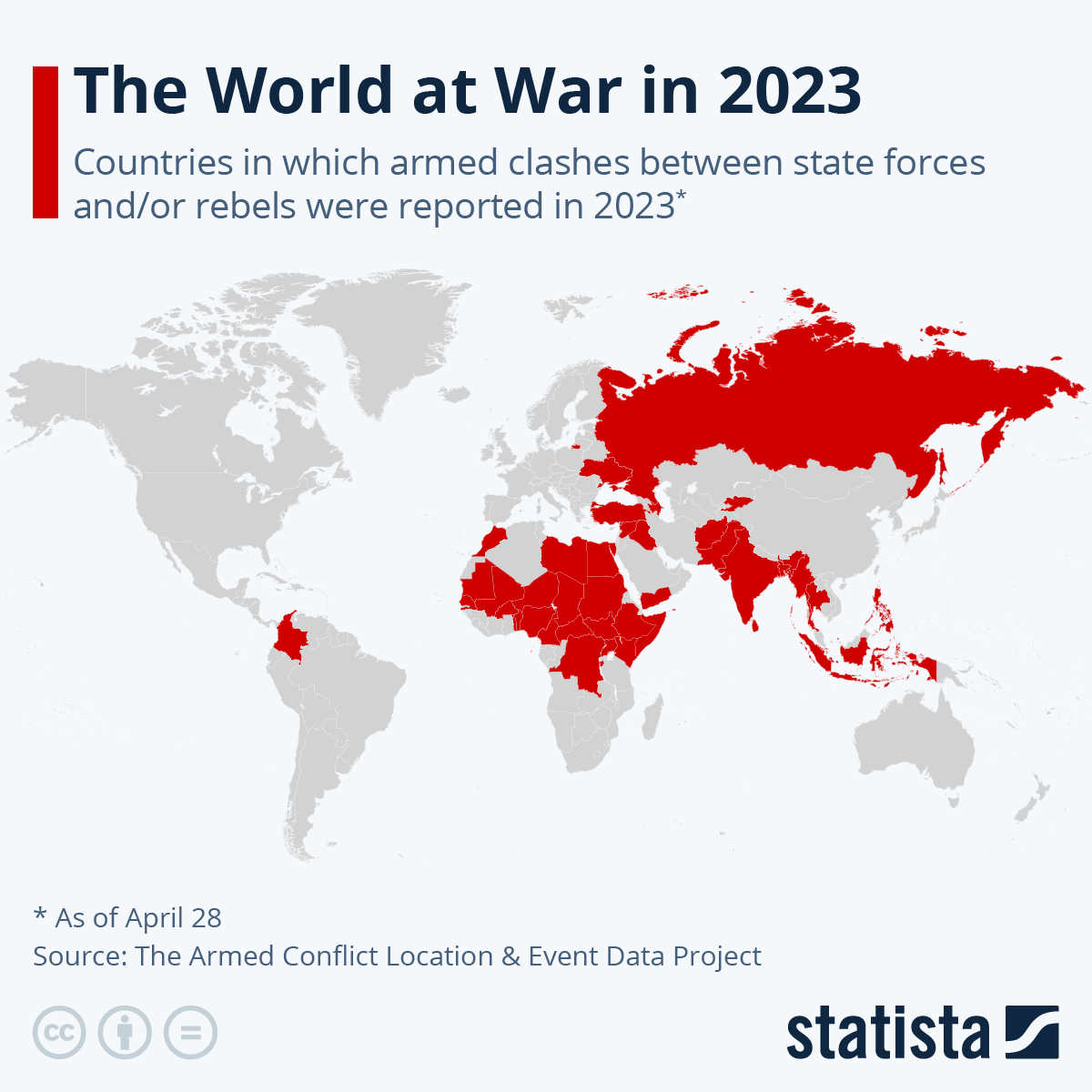

Today, Pakistan is going through a serious crisis. No matter how grand the statements made by Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif, or how much he tries to assert dominance on the world stage in collaboration with China against India, he knows he is the leader of a fragile and deteriorating country whose very existence is under question. While Pakistan is certainly facing economic and political challenges, it is currently grappling with an even deeper ideological crisis—one more severe than that of 1970–71, when Pakistan was split and East Pakistan became the new nation of Bangladesh. As we know, Pakistan suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of India in that war.

The partition of the country and the humiliating defeat in war were major tragedies for Pakistan. However, it managed to recover and carve out a distinct identity as a powerful nation, becoming one of the few countries to develop nuclear weapons. Due to its geographical location, Pakistan remains a strategic focal point for major powers like the United States, Russia, China, and India. But today, Pakistan’s greatest challenge is not political or economic but ideological. This crisis questions the very foundation and purpose of Pakistan’s creation.

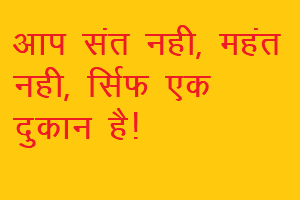

Ironically, this ideological questioning is not being led by Pakistan’s external enemies but by its own intellectuals and enlightened citizens. The anti-establishment media in Pakistan is openly asking: What has Pakistan achieved in the 78 years since its formation, and why has it fallen into such disrepair?

India, too, is grappling with issues of economic development and social cohesion. However, many Pakistani intellectuals and members of the outspoken media believe India has achieved remarkable success in comparison, despite both countries gaining independence from British colonialism at the same time. Even the two-nation theory of Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s founding father, is now being questioned within Pakistan.

Intellectuals and media in Pakistan are increasingly scrutinizing the country's achievements since its formation, particularly in light of its historical rivalry with India. The foundational ideology of Pakistan, rooted in the two-nation theory, is being challenged, with calls for a redefinition of national identity that embraces shared cultural heritage rather than enmity.

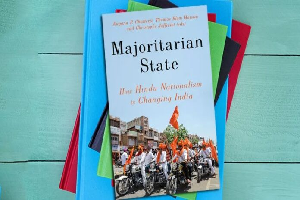

Senior journalist Husain Haqqani argues for a reevaluation of Pakistan's ideological framework, emphasizing the need for a constitutional foundation and a departure from religious extremism. The future of Pakistan hinges on whether this intellectual awakening can evolve into a broader national movement for change.

Some are now arguing that, regardless of how Pakistan was conceived or how the decision to partition India was made, the country should not have followed the path of religious extremism and enmity toward India. This approach, they claim, has harmed Pakistan and prevented its leaders from focusing on the critical task of nation-building—an oversight that today’s generation is now paying for.

Against this backdrop, a growing number of Pakistani intellectuals are calling for a redefinition of their national identity. A significant part of this reimagining involves ending blind opposition to India and Indian culture, and instead, recognising the shared historical legacy of the Indian subcontinent.

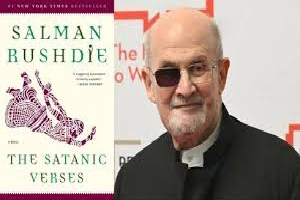

These questions and reflections have been encapsulated by senior Pakistani journalist, diplomat, and political advisor Husain Haqqani, who now lives in the United States to avoid persecution by the Pakistani establishment. Once a trusted advisor to the Prime Minister and former ambassador to the U.S., Haqqani has laid out his arguments in his book Reimagining Pakistan, calling for a redefinition of the country's ideological foundation.

Haqqani argues that 73 years after its creation, Pakistan has become an unstable, semi-authoritarian national security state that has consistently failed to function under constitutional rule or the rule of law. In his words, a semi-authoritarian state gives an illusion of freedom—it is not like the Soviet Union or Nazi Germany—but it is ruled by an elite that does not allow democratic change. Media appear free, but real debate is stifled. The military, a dominant arm of the state, has taken control of the entire country.

Pakistani nationalism is based on two key principles: that Pakistan is a land for Muslims, and that it is fundamentally different from India. This ideology teaches that Muslims could not coexist with Hindus, which justifies Pakistan’s creation. Consequently, school curricula in Pakistan exclude the histories of Sindh and Balochistan because these regional histories do not align with the ideological framework of the two-nation theory.

India still has a large Muslim population, yet Pakistan's Muslims were separated from them. The logic then became: since we’ve created a separate state, it must constantly be in a state of defence against India. This necessitated a dominant military presence. To match the size and strength of its army, Pakistan also needed to create corresponding threats. This led Pakistan to evolve into a semi-authoritarian national security state.

Crucial questions were never addressed at Pakistan's inception: What ideology should underpin the new nation? Why should it be an Islamic state? What should an Islamic state look like? What is the nature and purpose of such a state? What should the balance be between the federal government and provinces? Is perpetual hostility toward India necessary? Unfortunately, none of these questions were answered, which is why Pakistan never received a constitution like India’s. India had its constitution in just two years after independence, but Pakistan did not.

Is Pakistan an Islamic state, or simply a state for Muslims? If it’s the former, then Islam is universal, regardless of whether its followers are black Bengalis or white Europeans—so why should it be a centralised state? Why should this not be debated?

Instead of making a constitutional decision first, Pakistan allowed the military to intervene in politics. Continued enmity with India further empowered the military. In the early years, many leaders who had championed the two-nation theory came from Indian provinces like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. When they migrated to Pakistan, they found no political base in regions like Punjab or Sindh. To gain popularity, they relied on religious extremism.

The growing discontent in East Pakistan, military repression, and the 1971 war that led to Bangladesh’s formation struck at the very core of the two-nation theory. It became clear that religion alone could not form the basis for nation-building. One might have expected Pakistan to distance itself from religious ideology after this, but the opposite happened. Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, to assert dominance and cover up the humiliation of defeat, leaned heavily on religion. Even after the Simla Agreement, he talked about a thousand-year war with India and passed laws declaring certain Muslim sects as non-Muslim.

Though Bhutto was liberal by nature, political insecurity led him to align with religious extremists. Thus, Pakistan lost yet another chance to build a modern and progressive nation. Bhutto, though a popular leader, was partly responsible for the creation of Bangladesh. If he had allowed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman of the Awami League—the majority winner in the 1970 elections—to become Prime Minister, military oppression in East Pakistan and the eventual creation of Bangladesh might have been avoided. Bhutto’s insecurity may also have stemmed from his Sindhi identity within a Punjabi-Pathan military-dominated structure, and the fact that he had lived in Mumbai until the time of Partition.

Bhutto wasn’t the only leader who tried to build modern Pakistan while riding the wave of religious sentiment. The first mistake was made by none other than Pakistan's founder, Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Though he was a secular man with little interest in religion, he played into the hands of the religious clergy. Today, Prime Minister Imran Khan is repeating the same mistake—and he will likely pay the price for it.

Pakistan's enlightened class is now asking all the uncomfortable questions that the ruling establishment cannot answer. Overseas Pakistanis and those working abroad are also dismayed that Pakistan is viewed with contempt internationally. Comparing themselves with India only deepens the sense of despair among Pakistanis.

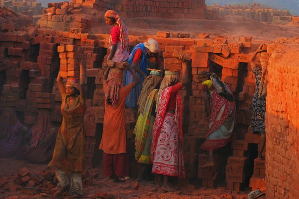

The root of the problem lies in the fact that after conceptualising Pakistan, there was no serious thought or effort toward building a nation. The country’s foundations were laid on religious extremism, Hindu opposition, and emotional fervour, but there was no in-depth study or plan to shape Pakistan into a functioning nation. Pakistan's first constitution came 15 years after its creation and was repeatedly amended. As a result, no path for development or institutional structure could be established. The colonial institutions of British rule were retained, but these were not suitable for a new nation. Land reforms and education were neglected, and no roadmap for economic development was created. A large portion of limited resources was spent on the military and arms. The consequences of this neglect are now apparent to all.

Pakistan is a major global player in terms of population, land, military strength, natural resources, and geographical importance. It could easily be considered among the world's top ten nations. Hence, Pakistan’s current crisis is a matter of global concern. It requires reflection by the entire global intellectual community. The question now is: Can Pakistan be redefined as a nation?

First, this work must be undertaken by Pakistan itself. If external intellectuals, political analysts, or researchers are to help, the ruling class of Pakistan must seek their assistance. But does the ruling elite even realise that the lack of a sound ideological foundation is what has led the nation astray?

Pakistan’s intellectuals now understand that their backwardness in development is due to ideological emptiness and confusion. These issues are raised candidly in media seminars and public lectures. However, this class remains small and has very limited influence over the broader population.

The question now is: Will this realisation grow into a national consciousness and transform into a revolutionary ideological movement? Only time will tell.

**************