6

Today’s Edition

New Delhi, 6 March 2024

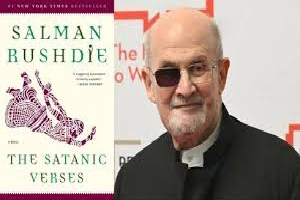

N Sathiya Moorthy

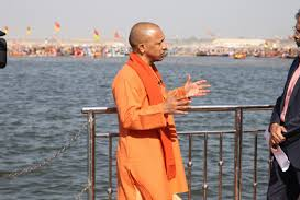

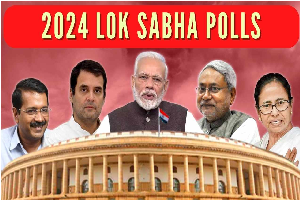

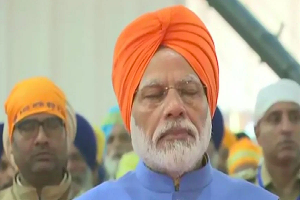

Many sections of the Indian media have highlighted one aspect of last year’s survey undertaken by the PEW Research Center in the U.S... The survey gives a high 79 per cent domestic ‘favourability rating’ for Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the third highest globally after Indonesian President Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo (89 per cent) and his Mexican counterpart Andrés Manuel López Obrador (82 per cent).

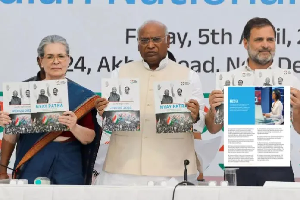

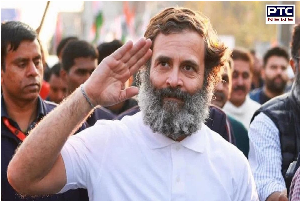

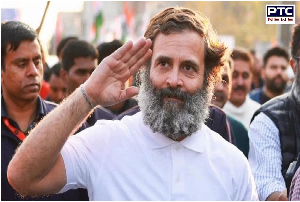

The same survey, when extended to Opposition leaders, makes former Congress president and the party’s unnamed prime ministerial candidate Rahul Gandhi as among the third ‘favourably’ seen leader in the pack at the global level. A very respectable 62 per cent of Indians surveyed had a favourable view of Rahul, followed by two other, much-less known party colleagues, Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury, the Congress leader in the Lok Sabha (42 per cent) and party president Mallikarjun Kharge (46 per cent). The three were among the 33 Opposition leaders surveyed across nations.

According to published accounts, both the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the opposition Indian National Congress (INC) had a rating of 73 per cent and 60 per cent respectively. However, 36 per cent of Indians held an unfavourable view of the INC while it was 25 per cent for the BJP. To the extent that the survey focussed on the ruling party and its charismatic prime minister in the country is understandable. But for the survey to consider only the Congress as the legitimate Opposition worthy of consideration despite having a low 52 seats in the Lok Sabha would require some explanation, after all. The survey likely considered India as the world’s largest democracy and the INC as the only Opposition party with a national presence.

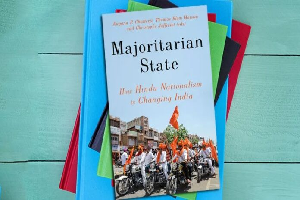

Authoritarianism or what

What is interesting to note even more is the fact that 72 per cent of the respondents in the country are satisfied with the current system of democracy. A high 85 per cent of the Indians surveyed said that either military rule or rule by an authoritarian leader is good for the country. Of course, there were variations in the choice regarding direct military rule and rule by an authoritarian leader with some legal backing.

It is surprising that ‘pro-democracy’ sentiments seem to have waned in the country over the past six years and noticeably so. The last time the PEW survey on democracy was conducted was in 2017, and the figures speak for themselves. Thus, 44 per cent of Indians thought that ‘representative democracy’ was a ‘highly effective form of governance’ in 2017 down to 36 per cent in 2023.

What is even more interesting or ironic is the fact that 14 per cent of Indians thought that allowing experts to make crucial decisions was good for the country in 2017. It went up to a very marginal 15 per cent in 2023. But for those who thought that rule by elected leaders, and not experts, was a better option, the figure went up from 65 per cent to 82 per cent.

Mixed bag?

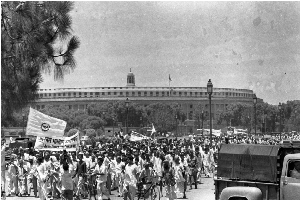

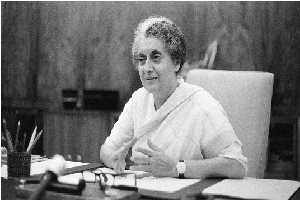

In a way, it is a mixed bag for democracy in India, one may conclude for the present, at the very least. That is to say, Indians want democracy, yes, but also a strong leader who could be walking the thin line in matters of democracy. In a way, it fits into PM Modi’s style of functioning. In the past, it fitted Indira Gandhi’s tenure as PM, especially in the seventies. That was when she proved her charisma in the Lok Sabha polls of 1971, which she had advanced by a year. It went on until her massive electoral defeat of 1977, at the end of the emergency.

It is unrealistic to consider it as a victory exclusively for democracy as the people waited to give their verdict on Indira Gandhi disregarding the Allahabad High Court unseating her as an elected representative, owing to ‘corrupt practices’ in the very same polls of 1971. Instead, it also owed to the people’s perception of government high-handedness in otherwise acceptable programmes like family planning (nasbandi or forced sterilisation) and urban planning that ended up as the ‘Turkman Gate incident’ in the capital Delhi, where again minority Muslims were the target.

Elections-77 showed that Muslims were not the only ones who were opposed to the ruling Congress Party at the time. This was even though for the first time since Independence (and possibly, earlier too), Indians saw trains running on time, offices filled with staff ever eager to oblige the citizenry, and supplies available in all shops across the country, no talk of hoarding or black-marketing. The unseen hand from above ensured that India moved on. Yet, the voter had a different take – and it did not stop with disgruntled government employees, bank and insurance unions, and the Railways staff, all of whom the emergency regime had ‘disciplined’, after all.

So personal, but...

PM Modi and his very effective propaganda team, starting with the BJP’s IT wing, may have convinced the contemporary generation that the Congress and all the regional parties are ‘dynastic’. It is a point that cannot be counter-argued. But it can be argued that if the question is one on the deification of the leader, neither the BJP nor Modi’s following outside of the party structure that the BJP can now co-opt as theirs, can deny it is not there.

What the Congress did to a dynasty, if that is the word, then the BJP is doing it to an individual. Today, the BJP wants Modi more than the other way around. It is evident too in the party’s behaviour, which is unlike even in the heydays of the Vajpayee-Advani duo. By the very definition, the existence of two strong leaders of equal standing with personal following inside the party was mostly invisible from the outside.

It is unlike the Modi-Shah duo who also weld into one, but the question of equals does not arise. The greatness of Vajpayee and Advani owes to the readiness with which each lent space and respect to the other and worked as a team. It became so personal that when some people close to Vajpayee spread canard about Advani’s family members, the Prime Minister took it upon himself to visit his deputy’s home without notice (and when the other man was way away), to apologise to the women of the house for what he did not know was happening. The greatness of Advani resided also in the fact that he did not seem to have made an issue of it even in private.

Today, the RSS monolith which told PM Vajpayee and other BJP leaders of the yore as to what they should do, when and how, is moribund. Modi, and not Mohan Bhagwat, is the boss, and Delhi and not Nagpur, is the capital. The RSS has understood its limitations in the new century and has readily adapted itself to the changing scenario. It seems to have slowly but surely understood that it is only a vehicle for the BJP, its creation, to achieve political power. Once it had acquired stability and continuity, the ideological parent had to take a back seat, as happened to the INC with its ‘democratic socialism’ of the Nehru era.

The BJP may lose elected power in a future election, if not this summer, and may even be down and out at some point, but the RSS is not going to be what it used to be. Yes, when the party has lost, then someone will say it all owed to the lack of ideology and direction. They did it after the failure of the Janata Party experiment (1980) when the ideological parent wrested the initiative from the political arm without effort. It is not going to happen another time.

Gentle colossus

When it is a matter of deification if that is the word, then it does not stop with Modi or Indira Gandhi, who acquired it through the poised valour of leadership during the ‘Bangladesh War’ (1971) and later through ‘Pokhran-I nuclear tests (1974). Yet, when it came to what should qualify as ‘domestic issues’, as the PEW survey showed decades later, the people voted her out in the next available opportunity, which came about only post-emergency, in 1977.

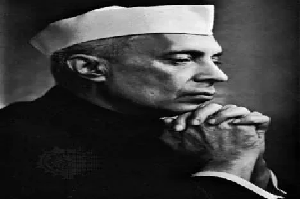

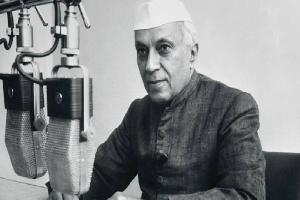

Before Indira Gandhi, there was her father Jawaharlal Nehru, who was a ‘gentle colossus’ in his lifetime, as some biographers put it. But even then some had the gumption to ask the question: ‘After Nehru, who?’ That India did not end with Nehru is proven beyond doubt, yet, in his time, Nehru’s charisma was too big for his political good and that of the nation. His mistakes during the ‘China war’ of 1962 proved precisely as much – but then he did not have the kind of team and believers who tried to white-wash his mistakes.

That is where the basic Congress’ character as an umbrella organisation for opinions and ideas came in. When the Congress Party lost that basic characteristic over time, whatever the external stimulant, then the party lost. The reverse is true of the RSS as the ideological parent of the BJP.

The right man at the right time

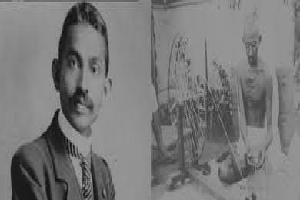

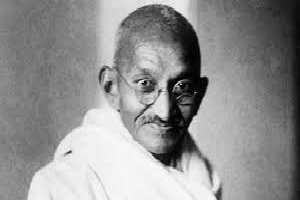

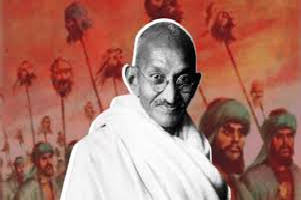

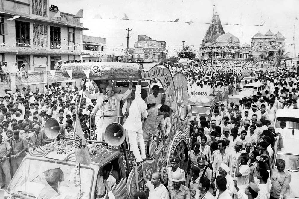

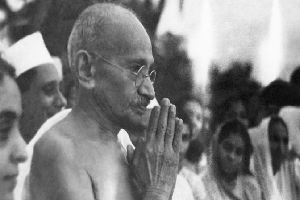

Before Nehru, you had the one and only Gandhiji, the Mahatma. Leave aside the politics that he promoted and the ideology that he propagated. Here was a man, who in an era far away from the present IT era communication and manipulation facilities, could reach out to the people – and spoke their language. The greatness of Gandhiji lived in his ability to comprehend what suited his land and people in his time, and not what would not be acceptable to them, at times even comprehensible to them.

Gandhiji was the right man at the right time and in the right place. He filled the leadership vacuum in the Congress, which had remained one ‘of the babus, by the babus, for the babus’. The rest, as they say, is history.

Look at it this way. Gandhiji and Adolf Hitler belonged to the same era. Both entered public life in their native countries almost around the same time. Hitler wanted Germans to rise in arms against the humiliation meted out to his people and nation by the leadership signing the humiliating ‘Treaty of Versailles, in 1920. They obliged. Gandhiji instead asked his people not to take up arms against the colonial British rulers. His Ahimsa and Sathyagraha won in his country, in his circumstances.

Imagine a reversed situation in which Gandhiji had asked Indians to fight with arms and Hitler had asked Germans to go to war unarmed and staged peaceful street protests for years on end. Both would have failed at the end of the first week, if not earlier. Gandhiji understood that his people had been subjugated for at least a thousand years, from the ‘Slave Dynasty’ in the 13th century if not earlier through the Guptas and Mauryas, where again the ruler and the ruled classes were well-defined and better delineated.

The Mahatma was the first ever deified leader of South Asia – and none other may have emerged since with the same reach and out-reach that belonged to a different generation, different set of tools. In the absence of prop-ups that began appearing in subsequent generations to the present – and possibly into the future – being genuine and looking genuine to the cause, purpose and methods alone counted in his time. That alone made sense.

Yet, there is no denying that Gandhiji was deified, and possibly that deification at least in part contributed to the nation’s freedom. If there was one man that the colonial rulers feared in his time, it was Gandhiji, the moral standing he took – and made his people take, alongside. By adding a touch of religion that he took, by preaching communal harmony in those difficult times of Partition and that which led to it all, he espoused a cause that was readily identifiable to the masses.

Yet, Gandhiji’s Ram and Gandhiji’s Ram Rajya were much different in form, content and spirit than that Modi espouses just now. Yet, he is as charismatic, and possibly more in percentile and real terms, as most Muslim critics of Gandhiji are now in Pakistan (and later-day East Pakistan, now Bangladesh). And the post-Partition Indian population too has multiplied many times over.

That difference and differentiation in the appreciation of Gandhiji’s Ram and Modiji’s Ram should explain how something like the PEW survey says that the 21st century Indians are comfortable with the idea of ‘authoritarianism’, in whatever form. That is also what makes the difference between the deification of Gandhiji in his time and Modiji in his time! (Words 2135)

***************

(The writer is a Chennai-based policy analyst & political commentator)

---------------