10

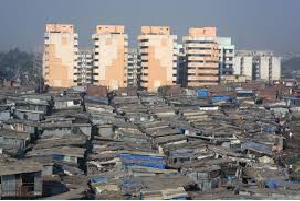

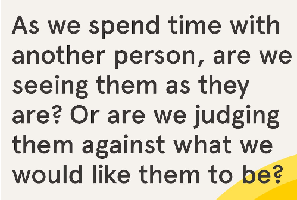

Stock markets and finance are infamous for manipulation, but few expected India's education sector to be just as tainted. The NAAC bribery scandal has eroded trust in top-paid teachers and the system meant to uphold higher education, shape national ethos, and drive economic growth.

The moral foundation of education has been shaken. If corruption can infiltrate a system built on ethical principles, it risks undermining every sector, leaving the economy even more vulnerable.

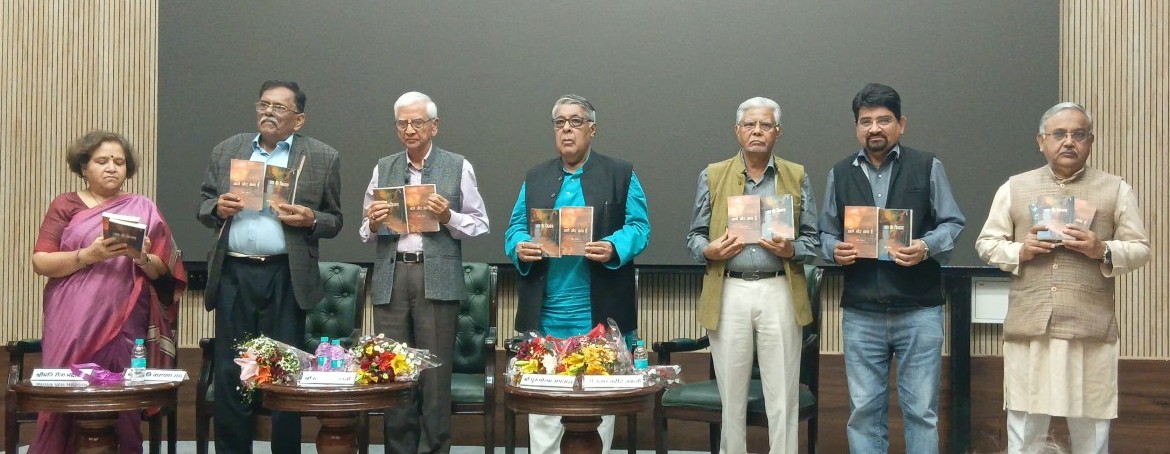

Now widely known as the NAAC-Koneru Lakshmaiah Education Foundation (KLEF) bribery case, the scandal involves 14 top academicians, including a mastermind from Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU). It exposes not just deep-rooted corruption but also its widespread prevalence in India’s education system.

As a direct fallout, NAAC has dismissed around 900 assessors—senior professors earning Rs 3 lakh or more per month with numerous perks—over the past few months. The exact financial scope of the NAAC bribery network is yet to be assessed, but estimates suggest it runs into billions. The CBI’s investigation into the Andhra-based KLEF scandal alone yielded Rs 37 lakh in cash, six Lenovo laptops, an iPhone 16 Pro, and incriminating documents. Raids across 20 locations in India are still ongoing.

Concerns about NAAC’s credibility are not new. Two years ago, a private university in western Uttar Pradesh—lacking even basic infrastructure—was controversially awarded an 'A' grade, raising suspicions of systemic malpractice. NAAC itself now admits to large-scale illicit transactions in exchange for higher grades.

Since 1994, all higher education institutions in India must seek NAAC accreditation. The country has 1,113 universities, including central, state, deemed, and private universities. There are 56 central universities, 455 state private universities, and 15,501 private colleges and institutions. Many institutions have gone for reassessments, further deepening the scope for corruption.

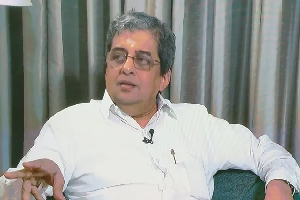

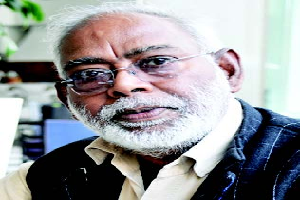

Deepesh Divakaran, a Board Member in leading institutions partnering with 300 academic bodies, calls it one of the most corrupt systems. He believes the KLEF bribery case is just the tip of the iceberg.

“This (KLEF) was not a one-off incident. I have personally witnessed numerous cases over the past decade that expose the deep rot within NAAC’s accreditation process. One of the first things I discovered was the existence of a parallel market of middlemen—individuals and agencies who guarantee NAAC accreditation in exchange for hefty sums. These brokers are well-connected with NAAC insiders, ensuring institutions get the grade they desire rather than what they actually deserve,” Divakaran states.

He adds that education sharks openly state, “Tell us the cost, and we will have our desires fulfilled.” The scandal is serious because it compromises institutions meant to build future citizens and create a clean society. Instead, these institutions prioritize profits over ethics, indulging in unholy practices.

The NAAC is a public autonomous central government body that assesses and accredits higher education institutions (HEIs) in India. Its rankings determine fee structures, facilities, and student intake. The rating system was supposed to provide transparency, particularly for private institutions, but the present scandal has raised questions about its credibility. Should such a flawed system even exist? Can private educational institutions be trusted?

There are no allegations of political motivations in this case. The findings are based on investigations that led to the immediate arrest of 14 teachers from various institutions, including JNU, Bangalore University, and Davangere University. A Bangalore-based NAAC advisor is also implicated. One teacher allegedly demanded Rs 1.8 crore to approve the gradation of a private university in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, though the final deal was reportedly settled at Rs 28 lakh.

NAAC and the National Board of Accreditation assessments are critical for institutions. However, unusual practices are common for securing top grades. The UGC and AICTE are unable to control it. Although NAAC’s Peer Team selection is supposedly computerized, in cases like KLEF, members were handpicked by NAAC officials. This raises concerns about peer team members having prior relationships with faculty members of the institutions they assess.

Divakaran quotes an agent who claimed, “Why bother with complex documentation when I can get you NAAC ‘A++’ for ₹50 lakh? If you want a hassle-free process, let me handle it!” Such statements reveal the widespread nature of peer review manipulation.

Divakaran recalls an institution where he served on the advisory board. The chairman casually stated, “We have already selected our peer review team. They are our people. The report will be favorable.” Such experts abound in the accreditation market, and agents with NAAC connections frequently visit private universities.

Several institutions fabricate research papers to boost their NAAC scores. Despite poor faculty wages, institutions spend vast sums on deception. They buy fake indexed research citations and publish plagiarized work in journals, turning academic publication into a parallel industry. Even amid a recruitment crisis, institutions present immaculate placement records and feedback reports.

The accreditation system, along with its record-keeping and paraphernalia, has become a costly, redundant process that questions its necessity. It has evolved into a review mechanism that prioritizes paperwork over academic delivery, with many institutions functioning as degree mills, particularly with the rise of online education.

The Ministry of Education must take decisive action. Rather than persisting with a flawed accreditation system, it should ensure institutions prioritize academic integrity and genuine learning. Cleaning up this deeply entrenched corruption is essential to restoring credibility in India's education sector.