21

New Delhi, August 21, 2023

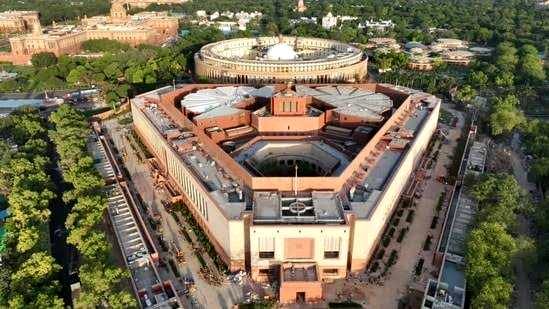

Ironically, life-sized portraits of the Mahatma and Savarkar face each other on the cylindrical walls of Parliament. And occasionally, temples are built to the glory of Godse.

John Dayal

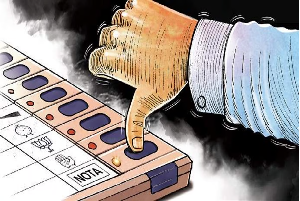

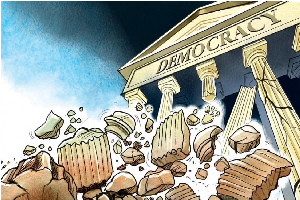

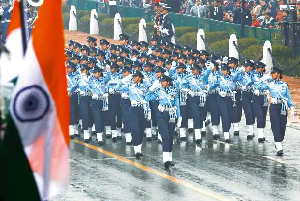

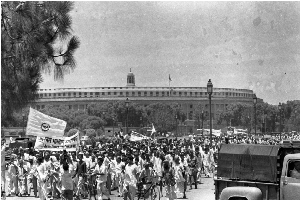

India became 76 years as an independent country on 15th August 2023. It approached the day with its civil society and religious minorities apprehensive that a continuing effort by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government to domesticate its Supreme Court and Election Commission /will irretrievably upset the delicate equilibrium between constitutional institutions, spinning India in a trajectory far from the unique democracy it sought to be surrounded by dictatorships and theocracies.

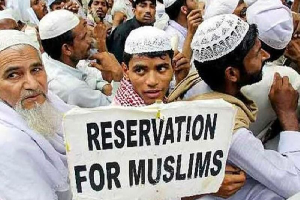

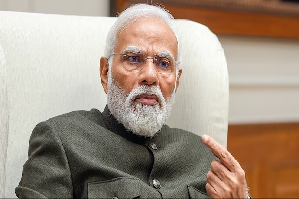

A billion-strong Hindu theocracy with a nuclear muscle is the dream of the militarist Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), which delegated a powerful member, Narendra Modi to national mainstream politics. Modi, who parachuted as chief minister of Gujarat at the turn of the century, has not been able to wash off the infamy of presiding over a pogrom against the state’s Muslim population in 2002. Modi, came to power in May 2014 riding an acrid election campaign targeting Muslims as anti-nationals, won a second term in 2019, on a similar platform.

Almost as an aside, Mahatma Gandhi was assassinated on January 30, 1948 by Nathuram Godse, a fanatic supremacist who thought the ‘Father of the Nation’ was soft on Muslims. This he had learnt from V D Savarkar, once a campaigner against the British and later their apologist, and “Guru” Golwalkar, a founder of RSS. Both saw an India where the Hindu ruled as he did in the mythological golden age, and Muslims and Christians, if they wanted to reside, had to accept they would have no electoral franchise, and would be second class citizens at best.

Ironically, life sized portraits of the Mahatma and Savarkar face each other on the cylindrical walls of Parliament. And occasionally, temples are built to the glory of Godse.

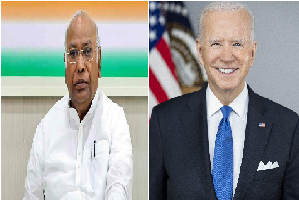

And in the last nine years, Narendra Modi has done his best to assassinate the character and shatter the political contribution of Jawaharlal Nehru, the man credited with laying the foundations of a credible democracy with the potential of science, technology, and academic excellence. Modi has not fully succeeded in photo-shopping Nehru out of public memory, but sometimes it seems he is getting there.

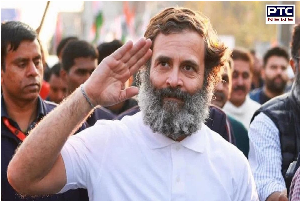

The only visual one sees in the country is the visage of the prime minister, on billboards of various sizes, his silver beard too waxing and waning as he appears now as a paternal and benign philosopher king, and then a general commanding a vast army, and occasionally the scientist-engineer on the wheel of the ship of state. A generation of young Indians now entering their twenties have seen no other political face.

Now at the peak of his powers, and described dictatorial by his critics, Modi has an Election Commission licking out of his palms, and a Council of Ministers which knows its place now as a mere rubber stamp. Modi has all but formally launched his campaign for a third term in 2024. The tried and proven ingredient of Islamophobia now also has a supporting tirade against Christians for luring Hindus to the church by dollar driven conversions.

The targeted hate against Christians has led to a vulgar rash of violence against children, women, men, and clergy, Catholic and Protestant, in small towns and villages in the two focal states of Chhattisgarh and Uttar Pradesh. The threat to make these states “Christians-free” must be taken seriously. Human rights groups such as Open Doors, Persecution Relief, United Christian Forum, and the Evangelical Fellowship of India estimate the number of violent incidents against Christians could be possibly as high as 1,500 to 2,000 in 2022.

Christians this month have staged protests in almost every major metropolis against the massacre of the Kuki Zo tribals, all Christians, at the hands of the plains-bound Meitei in the northeastern state of Manipur. More than 150 are dead, and over 50,000 displaced. Over 350 churches are destroyed. Civil society warns of a national health crisis in the children and young living in a100 refugee camps run by small churches in the hills inhabited by the Kuki.

The new year began on disastrous with at least two thousand Christians fleeing their villages in Chhattisgarh as mobs yelped for blood. The Christians were offered the choice of life as a Hindu, or death or exodus if they remained faithful to Christ. India has no respect for data, and figures for everything from Covid fatalities to deaths by hunger or malnourishment remain tentative because no one really finds what caused the death of persons who pass away in the hinterland. In case of sectarian violence, the police, most often than not, victimizes the wounded, and would rather not register a case against assailant attacker unless civil society raises a red flag.

Rapidly weaponized laws against conversions have made a mockery of the rule of law. “Cow protection” lynch mobs terrorize Muslims, occasionally killing Christians as well. “Ghar Wapsi” gangs, or “home-coming” activists, mainly target Christians, with their vocal mission to convert old and new Christians to the Hindu fold. The laws permit the conversion to Hinduism. The police and civil authorities help along.

A timid civil society, with only isolated individuals of courage, and no real powerful institutions to resist this onslaught, would also coin slogans on safe issues such as climate change rather than the thousand sharp cuts on the body politic. Every valiant Harsh Mander, Fr Cedric Prakash, lawyer Colin Gonsalves, or Teesta Setalvad and Kavita Srivastava are more than countered by a somnambulant National Human Rights Commission and a lapdog national media.

Mander, who has escaped death twice from Covid and complications of the heart, lives a life hounded by the federal investigating agencies seeking to indict him for conspiring against the state or cheating. Teesta is currently out of jail on bail ordered by the Supreme court. Her crime: enabling a Muslim woman, Bilkis Bano, gangraped in the Gujarat 2002 violence by her neighbors who also killed her children and many relatives, to seek justice in a court of law.

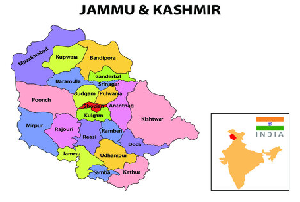

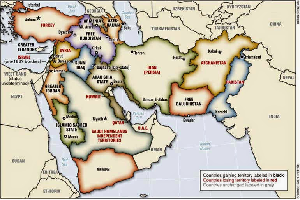

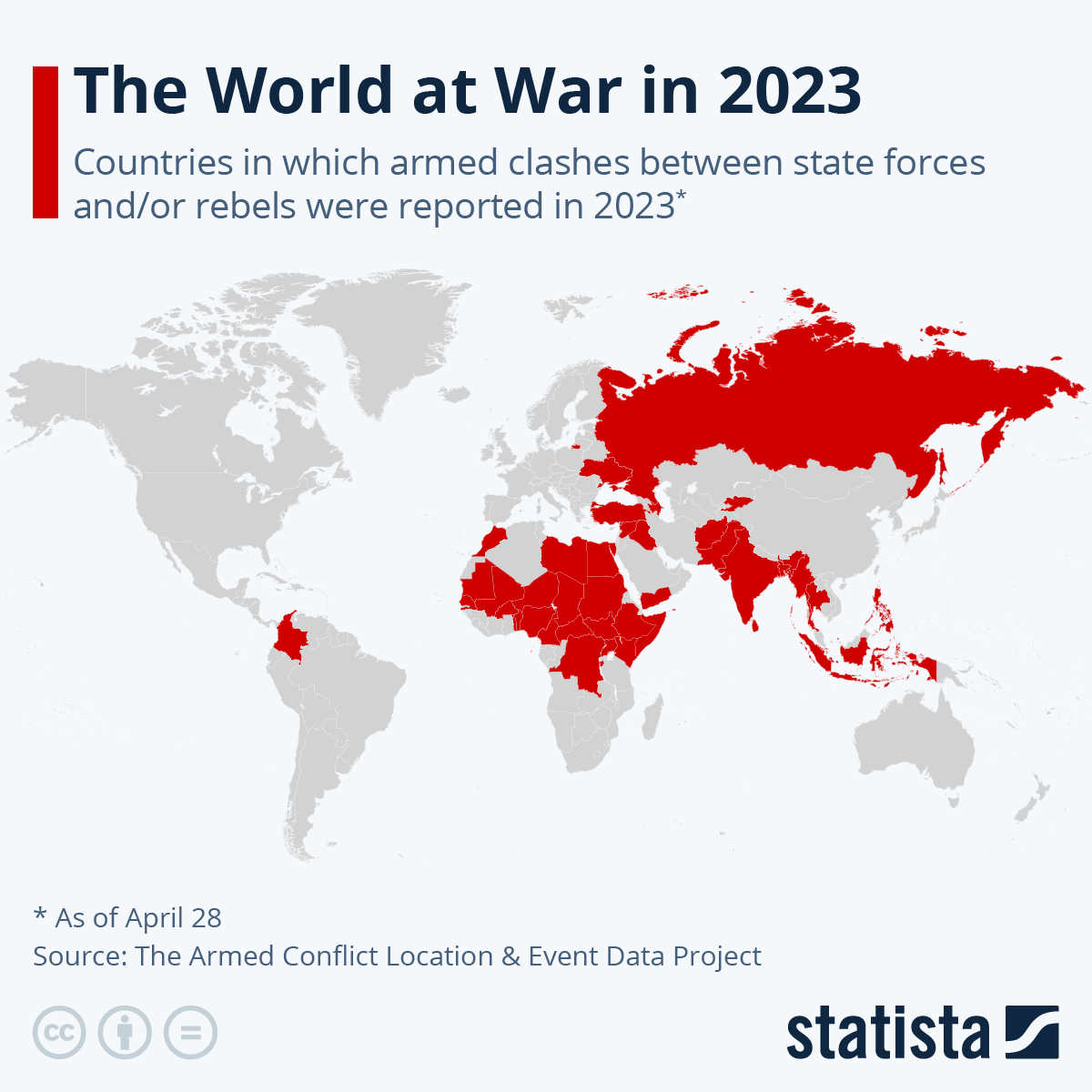

The scenario may alarm activists, church leaders and the intellectual, but it quite fits into the fantasy of Hindu Rashtra, a larger theocratic state eventually spanning the south Asian landmass and undoing the 1947 Partition of British India. The racial memory of that has fueled Muslim-Hindu violence over the decades, and the India Pakistan military confrontation with its own bloody trail.

Christians are collateral damage. They are seen no more than as political trash remaining from the colonial era, and new followers of Jesus Christ as purchase of the rich West. Death, injury, and vandalism is dismissed as occasional and unconnected. International, even United Nations’ statements on targeted hate and violence are dismissed as an interference in the internal affairs of the world’s most populous and benign democracy. The prime minister and the government remain in a state of denial.

Political observers and social activists have long warned that any attempt to change the “secular” nature of the Indian state, especially guaranteed by its constitution, will be disastrous. This is not just to save the large Muslim and Christian minorities, estimated to be now collectively close to 250 million in a 1.30 billion nation, but for peace in the subcontinent where both India and Islamic Pakistan have an undisclosed number of nuclear warheads and delivery systems.

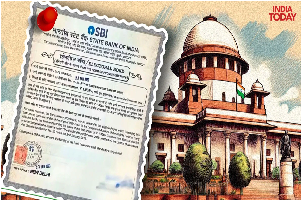

Stopping the sword play between Modi’s cohorts and the Supreme court, if not bringing them to a lasting truce, is critical in this. The independence of the judiciary, now safe in the collegial system of choosing fresh talent to the High Courts and the Supreme Court without political meddling, in turn protects the Constitution from political and executive sorties to cut into its core structure of freedoms, equality, and fraternity.

The independence of the judiciary is guaranteed by the State and enshrined in the Constitution or the law of the country. It is also mandated of the United Nations. On January 18, 2023, one of India’s most celebrated judges, Madan Lokur said suggestions made by the then law minister Kiren Rijiju to the Chief Justice of India about how judges for both the High Courts and Supreme Court should be chosen are “unacceptable”. They would, if implemented, “damage and undermine the independence of the judiciary”

Justice Lokur said: “It’s an attack on the constitution … a veiled attack on the constitution through the medium of the judiciary”. He added: “It’s being done by the government … not the law minister on his own.”

Rijiju, no longer law minister but looking after earth sciences, still has now the strong support of the vice president of India, Jagdeep Dhankar who also chairs the Rajya Sabha - the upper house of Parliament. Addressing the 83rd All-India Presiding Officers Conference in Jaipur, the Vice President called for a debate to determine if the Parliament’s will can be subject to any other authority, including the judiciary. Dhankar questions the Supreme Court’s April 1973 verdict in the classic Kesavananda Bharati case that puts the basic structure of the constitution beyond the reach of parliament. Both Parliament and the Supreme court are creations of the Constitution.

No one doubts anymore that the present frame of the Constitution is the one thing standing in the way of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s dream of a Hindu Rashtra.

The Prime Minister, used a Constitution Day function by the Supreme Court to say “the whole world is looking at India with a lot of hope amid its fast development, fast-developing economy. Modi was kind enough to accept that the Constitution had something to do in this success. He called to attention to the first three words of the Preamble, ‘We the People’, and said it “is a call, trust and an oath. This spirit of the Constitution is the spirit of India that has been the mother of democracy in the world,”.

The words are beguiling. But the duel rages. And the people watch in trepidation as India inches to the 76th year of independence.

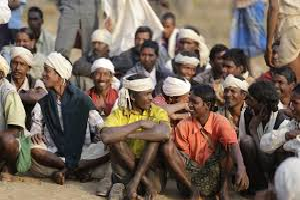

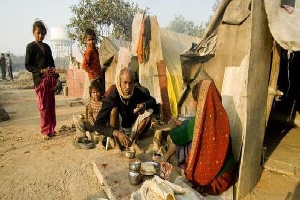

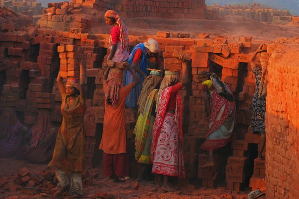

For them, the common people of the country, especially its religious minorities, its Adivasis and Dalits and the teeming rural and urban poor, the grandiose words in golden letters in a book, or etched in stone, translate into a simple right to live in security, with the means to bring up a family in human dignity and choice of faith and ideology. They do not want to look over their shoulder every so often to see if the next attack comes from the secret police or the crazed majoritarian mob.